Squid Game: How Playground Games and Candy Colors Became a Nightmare

Let’s be honest: when you first heard about Squid Game, you probably thought, “A deadly game show with childhood games? Sounds weird but kinda cool.” And then you watched it—boom. Total immersion. What Squid Game does so brilliantly isn’t just the violence or the twisted drama. It’s how it wraps that horror inside a candy-colored nightmare, using visual design and old-school games to say something disturbingly real.

So let’s break down two of the show’s most powerful tools: visual symbolism and the twisted use of traditional Korean playground games. There’s more going on here than just aesthetics or nostalgia.

The Visual Style: Innocence Meets Oppression

The first thing that hits you about Squid Game—before a single shot is fired—is the color.

Pink and Green Aren’t So Friendly Here

The guards in bright pink jumpsuits. The players in green tracksuits. It’s a stark, playful contrast that screams “child’s play,” but the context is brutal. The color scheme is straight out of a kindergarten, but the setting is life-or-death. That contrast is no accident. The show plays with our expectations—soft, comforting visuals used in the most sinister way.

The uniforms also establish hierarchy. Guards in faceless pink uniforms are anonymous tools of the system, while players are reduced to numbers in identical green outfits. You’re either controlling the game or trapped in it. No one’s really human anymore.

Shapes as Social Codes

Circle, triangle, square. You’ve seen those shapes everywhere—on the guards’ masks, on the doors, even on the business card. The inspiration? Think PlayStation buttons meets military insignia. In the show, they subtly represent rank and order:

- Circle = Worker

- Triangle = Soldier

- Square = Manager

The simplicity adds to the unease. It’s almost too clean, too sterile. And it feeds into the idea that everything—even life and death—can be systematized.

The Set Design: Childhood Memories with a Dark Twist

Walking through the Squid Game sets feels like being inside a warped schoolyard. But that familiarity is exactly what makes it so chilling.

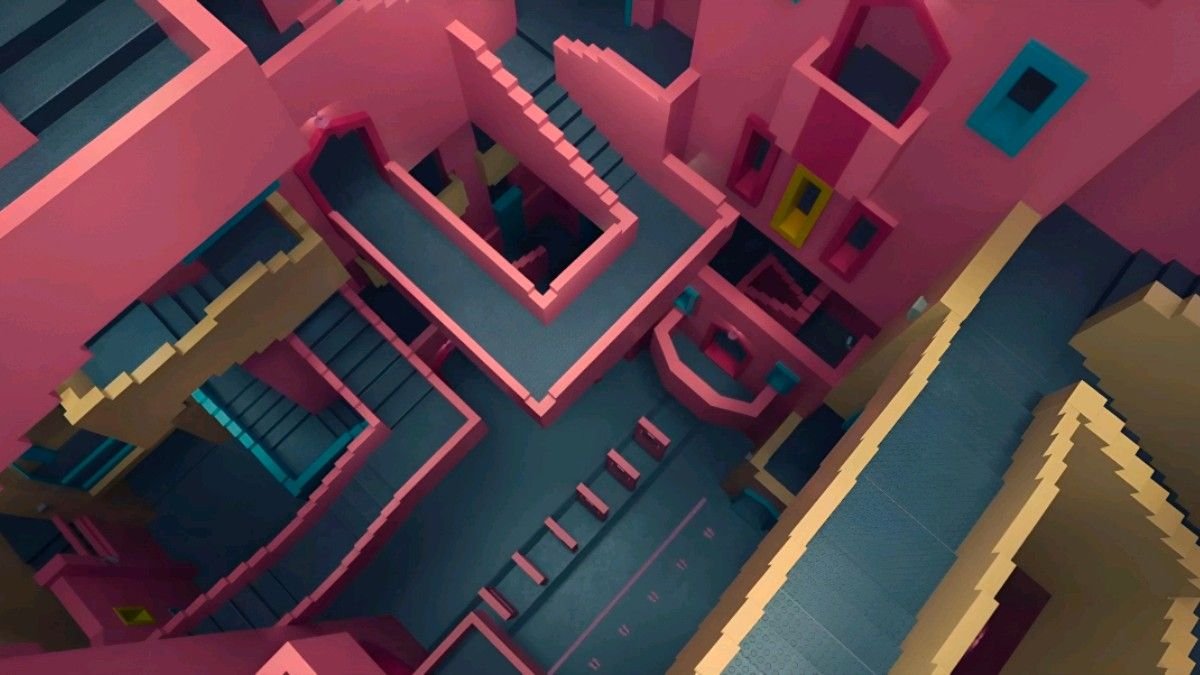

The Staircase from Your Dreams (or Nightmares)

Remember the pastel-colored Escher-like staircase maze? It’s visually inspired by M.C. Escher’s “Relativity”, but it also resembles a toy box. It’s disorienting on purpose—players are being funneled like cattle in a space that should feel safe, but doesn’t.

Oversized Props, Shrunken Humanity

In the Red Light, Green Light game, the playground is massive. The robotic doll is towering. The sandbox is vast.

Why?

It makes the players look small, helpless—like kids again, but this time without any adult protection. The show uses scale to belittle, to strip people of their autonomy.

The Dreamlike Maze of the Dormitory

At first glance, the players’ sleeping quarters just look like a giant gymnasium filled with stacked beds. But it’s deliberately sterile and dehumanizing. No privacy. No personal space. Just row after row of identical bunks.

As players are eliminated, the beds disappear too—literally. The shrinking number of bunks becomes a visual reminder of death. It also subtly shifts the atmosphere from “camp” to “cage.” By the end, the room starts to resemble a warehouse or a morgue. It’s a clever use of space to show rising tension without saying a word.

The VIP Room: Velvet and Voyeurism

Then there’s the VIP room. Animal masks. Gold furniture. Naked human furniture. It’s decadent to the point of grotesque.

This set is loud and intentionally vulgar. It’s meant to show how far removed the rich are from the suffering below. While the players fight to survive in brutal conditions, the VIPs lounge in velvet chairs, sip cocktails, and treat human beings like chess pieces.

It’s designed to echo old Roman gladiator arenas, where nobles watched people die for fun. The aesthetics scream wealth, but there’s no taste—just indulgence. A nice visual metaphor for unchecked power.

Surveillance Spaces: The God’s-Eye View

From the hidden control rooms to the camera eyes placed in dolls or walls, surveillance is everywhere. The design here is cold, gray, and minimal. Everything looks industrial. It reminds you that this whole system is mechanized. It’s not personal. It’s automated exploitation.

The show doesn’t just tell us people are being watched—it shows us how: constantly, from every angle, by people we don’t see.

The Games: Where They Came From—and Why They Matter

This is where Squid Game really hits home for Korean audiences. Every game used in the show is based on real children’s games popular in Korea during the 70s and 80s. For many viewers, these games were pure nostalgia. Until now.

Ddakji (딱지)

A Korean street game using folded paper tiles. You slam one ddakji on another to flip it.

The first taste of Squid Game’s twisted logic—you lose, you get slapped instead of killed. The game shows how desperation overrides dignity. You’re being tested before you even know you’ve signed up.

Red Light, Green Light (무궁화 꽃이 피었습니다)

You know the rules: move on green, freeze on red. But in Korea, the phrase used translates to “The hibiscus flower has bloomed.” It’s traditionally a harmless, silly game. Here, it’s turned into a sniper trial. This game being first was intentional—it lulls the players into a false sense of comfort, then shocks them (and us) with brutality.

Honeycomb (Dalgona) Challenge

This was a real candy street snack for kids in Korea. If you could poke out the shape without breaking it, you got a free candy. In the show? Break the shape, you die. The tension is absurdly high, but the task is absurdly simple. It’s a perfect metaphor for how society makes survival feel like a rigged game: one tiny crack, and you’re out.

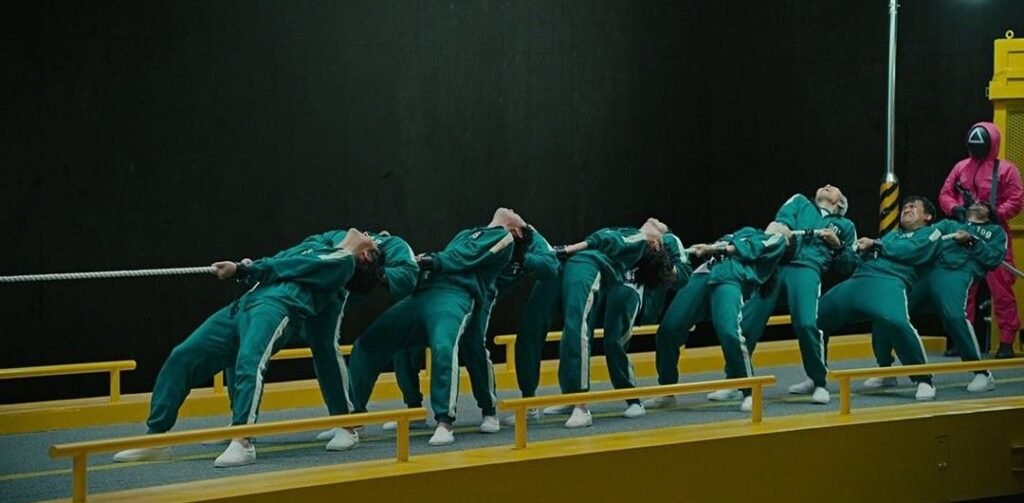

Tug of War and Marbles

Both games rely on trust and teamwork, which the show masterfully weaponizes. Tug of War originates as an universal childhood game involving two teams pulling a rope in opposite directions. It becomes a battle of life and death—won only through unexpected cooperation and strategy.

Marbles is even worse: it uses friendship as a setup for betrayal. It’s not just physical survival; it’s emotional devastation. Traditional marble games vary widely; kids invent their own rules. In Korea, marbles were a flexible part of street play.

Glass Bridge

Not a traditional children’s game. It’s an invented challenge inspired by video games or logic puzzles—each player must jump from pane to pane, hoping they choose the tempered glass. A game of pure luck disguised as skill. It strips away any illusion of fairness. Players can’t strategize, just survive. The order in which you play literally decides your fate.

The Squid Game Itself (오징어게임)

This was an actual game played by Korean kids, especially boys, in the ’70s and ’80s. It’s rough, aggressive, and requires strategy. In the show, it becomes the final battleground—fitting, because it was always a game of winners and losers. There’s no tie, no draw. Only dominance.

Scratch-off Bread Lottery

In S2 Ep 1, 100 unhoused people in a childlike setting are given a choice – Bread or Lottery ticket. If they choose bread, they eat. If they choose the ticket, they get a coin to scratch it, then must return the coin. No one gets both. Most choose the lottery. When it’s over, the Recruiter stomps on the leftover bread, mocking their choices and leaving a mess behind—for the birds and for the people watching. But his spectacle also gives a clear photo of players’ target.

Rock–Scissors–Paper (가위 바위 보) and russian roulette

The Recruiter introduces a twisted version of Rock, Paper, Scissors: each player uses both hands, then removes one, and the remaining hands decide the winner. It’s simple—until you lose. It is a universal hand game. Used between kids for fun or to make decisions.

The penalty? Russian Roulette. The Recruiter spins the chamber and pulls the trigger on the loser, assuring players it’s just a “one in six” chance. After a few rounds, he raises the stakes—loading five bullets instead of one. Obviously, it is not a children’s game. It’s a deadly adult game of chance and despair. Used to expose the psychological descent of people who become players or staff. It’s not for fun—it’s for survival, and the illusion of control when you have none.

Flying Stone

Players throw a stone to knock over another placed at a distance. If they miss, the entire team must walk to retrieve the thrown stone and start again. It’s simple, but exhausting. The game captures the futility of effort without progress—a clear metaphor for people stuck in systems where failure doesn’t just mean starting over, but dragging everyone else back with you. It’s a slow grind that mirrors life under relentless pressure.

Gonggi (공기)

A Korean game similar to jacks. Players toss and catch small stones in stages. It’s a test of dexterity and rhythm. The game looks silly, but it’s high-stakes now—emphasizing how innocence is weaponized.

Spinning Top

To win, players must wrap a cord perfectly around a wooden top, hold it just right, and throw it so it spins. If any part fails, the team must walk over, pick it up, and do it all again. This game is about precision, control, and repetition—and how fragile success is when everything has to go exactly right. It reflects the tension between individual skill and group burden, where one slip sets everyone back.

Jegichagi (제기차기

A Korean version of hacky sack. Players kick a feathered object (jegi) to keep it in the air. It looks easy, but demands intense focus and body control. Players are punished for minor failures—again emphasizing perfection or death.

Musical Chairs/mingle

A global party game. When music stops, grab a seat or you’re out. This version adds physical combat and deception. A symbol of cutthroat competition—the world is watching, and the seats are disappearing.

The Maze / hide and seek

The final game isn’t just survival—it’s about reflection, values, and what the winner becomes. The maze represents the system itself: shifting, manipulative, and rigged. A constructed, symbolic maze representing life choices. Players must navigate moral and tactical dilemmas—not just physical challenges.

Jump Rope (줄넘기)

Featured in flashbacks of children’s pasts, including Il-nam’s (creator and first host of the Squid Game) neighborhood. This classic playground game is a symbol of innocence and group fun—often associated with girls’ games in Korea. When referenced in Squid Game, it’s a visual marker of a time before everything became transactional.

Sky Squid Game (하늘의 오징어 게임)

A variation of the traditional Squid Game, played on rooftops or upper levels in apartment complexes. More dangerous due to the elevation. It reflects how even kids simulated risk and battle. In the context of the show, it reinforces the theme of structured violence starting young—only now, the “sky” part is real, and the stakes are death.

Why It All Works So Well

By choosing games rooted in childhood, Squid Game forces us to confront a twisted truth: the systems we play in as adults aren’t so different. It’s just that the stakes got higher, and the rules more invisible. You’re still being pushed to compete. You’re still being ranked, watched, judged.

And visually? It’s all packaged like a dream. Bright colors. Giant toys. Friendly shapes. But inside? It’s a nightmare of control, desperation, and survival.

Squid Game didn’t just succeed because it was thrilling or violent. It worked because it knew how to play with us—visually, emotionally, psychologically. It reminded us of childhood, only to show us how far we’ve fallen since then. That’s not just clever. That’s art.

Got a favorite game from the show? Or one you’d totally fail at? Let me know—I promise not to vote you out.

Images sourced from online platforms and Pinterest. Credit goes to the original creators.